Nautical History At The Marine Museum Of Manitoba

Ships and exhibits at the Marine Museum of Manitoba in Selkirk, Manitoba, Canada, showcase the nautical history of the Red River and Lake Winnipeg from the 1850s to present day

The waterways in southern Manitoba, Canada, have been important for transport, trade, and fishing for thousands of years. The Marine Museum of Manitoba tells the story of that nautical history focusing primarily on the Red River and Lake Winnipeg from the 1850s to present day.

The 885-kilometre-long Red River begins in the United States at the convergence of the Bois de Sioux and Otter Tail rivers on the border of North Dakota and Minnesota. It flows north into Canada and empties into Lake Winnipeg.

Lake Winnipeg is the 11th-largest freshwater lake in the world in terms of surface area. Sandy beaches, limestone cliffs, and boreal forests line the relatively shallow lake. The lake drains northward into the Nelson River and forms part of the Hudson Bay watershed. The Red River is one of its many tributaries.

The museum is located in Selkirk, about 35 kilometres (22 miles) north of Winnipeg, Manitoba’s capital and largest city. The Red River runs through Selkirk. The museum sits beside Selkirk Park on the banks of the river.

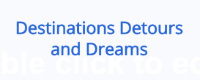

The museum consists of six historic ships parked on a grassed area. Visitors can board the ships to get a sense of what it would have been like to travel on them and see a variety of interesting exhibits.

S.S. Keenora

Is it a ship or a boat?

That question was on one of the first exhibits I saw when I boarded the Keenora. The answer was provided.

Answer: It’s your choice; there is no definite set of rules that makes the Keenora either a ship or a boat. If it helps, remember that a ship’s owner will be annoyed if you call his vessel a boat, but a boat owner will be pleased if you call his vessel a ship.

The main part of the museum is in the S.S. Keenora. Keenora was built in 1897 for service on Lake of the Woods. In 1917, she was cut in sections and shipped to Lake Winnipeg, where a 30-foot (9-metre) section was added. She spent one season as a floating dance hall, but by 1923, she was carrying passengers and freight to communities around Lake Winnipeg. In 1959, her steam engines were replaced by diesel engines. By 1966, she couldn’t meet new transport regulations and went out of service.

Why is a ship called “she”?

This question was also on one of the first exhibits I saw.

Answer: Some say that sailors thought of a ship as a mother; others say that ships were originally named for goddesses. The Royal Navy calls its ships “she”, as do the Canadian and American navies. Since 2002, Lloyd’s of London Shipping Register refers to a ship as “it.”

The purser was the only member of the Keenora crew who slept on the passenger deck.

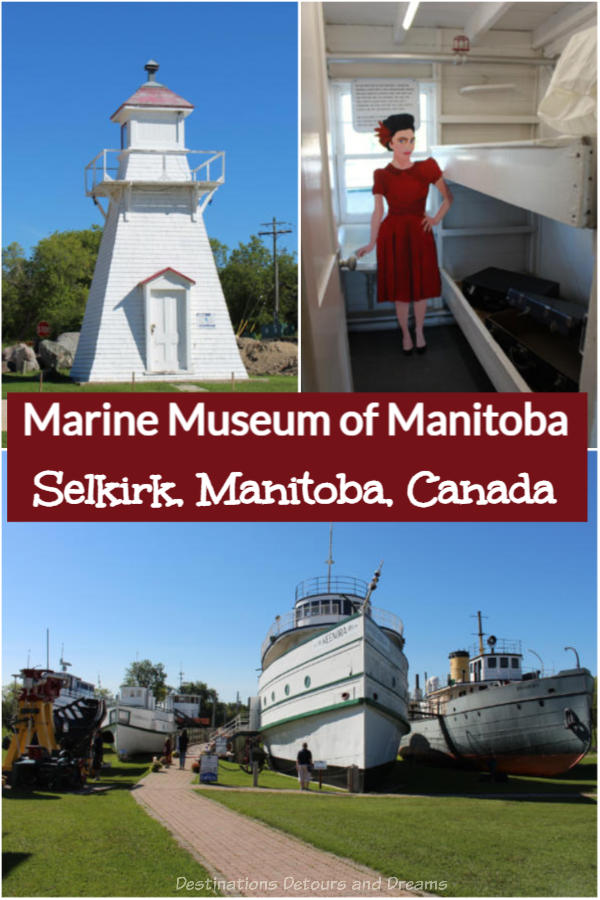

The Keenora accommodated 65 passenger cabins. The cabins are now exhibit rooms containing a variety of artifacts, photographs, and informational panels.

Topics highlighted in other exhibits include: Indigenous fishing and Indigenous communities along Lake Winnipeg, Lake Winnipeg ports of call, fishing and ice fishing, Lake Winnipeg resort and beach communities, crew uniforms, and Lake Winnipeg tragedies. (One of the steamboat captains claimed the Lake Winnipeg was the roughest lake in North America. It has been described as “moody” and “fickle,” turning from sunny calm to twenty-five-foot whitecaps in a matter of hours.)

Peppered throughout the displays are memories of former passengers and crew members. In the memory shared in the above photo, a woman writes about sharing a cabin with a disagreeable woman who had ordered a private cabin with bath, but was told that was not available. She said she was used to ocean liners and this was a comedown. She irritated the entire staff with her mealtime demands and bored the other passengers with her ocean liner tales.

A canoe-shaped lifeboat sits on the top of the Keenora.

C.G.S Bradbury

The Canadian Government ship Bradbury was pre-fabricated in Quebec and assembled in Selkirk in 1915. She was originally built as a fishery patrol vessel, but was not very successful as she burned coal instead of wood. The black smoke from her funnel gave poachers plenty of warning and she never caught anyone. Although not built as an icebreaker, she often acted as one. Her wrought iron hull could handle ice better than most boats on the lake. She was retired in 1973.

Peguis II

The Peguis II was a government tug built in 1955. She operated on Lake Winnipeg from 1955 until 1974 as a dredge tender. Dredges keep waterways navigable for shipping by bringing up bottom sediments and dumping them on barges for disposal at a different location.

Lady Canadian and Chickama II

The Chickama II, built by the Purvis Company of Selkirk, operated as passenger and freight vessel on Play Green Lake. She took cargo from the S.S. Keenora which was unable to navigate the waters of the smaller lake.

The Lady Canadian was a fish freighter built in 1944 by the Purvis Company and later rebuilt by Riverton Boat Works in 1963.

Joe Simpson

The flat-bottom vessel Joe Simpson, built in 1963, took over the duties of the Chickama II as a freighter taking cargo from Warren Landing to Norway House. She was named after a famous 1900s era hockey player, “Bullet” Joe Simpson, who was originally from Selkirk. When new roads opened up the north, boats like her were no longer needed. She was retired in 1975.

Other Exhibits

Other items found on the grounds of the museum include two authentic Lake Winnipeg lighthouses, a lighthouse keeper’s house where he and his family would have lived during the shipping season, the building that the Selkirk Navigation Company building, an old tramway, dredging equipment, a whitefish boat, and the engine, smokestack, winch, and generator of the last steam tug to operate on Lake Winnipeg.

The Jackie S, the last all-wood whitefish boat used on Lake Winnipeg, was built in 1952 in Selkirk by Gus Stephanson, who named the boat for his daughter.

Visiting the Museum

Allow one to two hours for your visit to the museum at 490 Eveline Street in Selkirk, Manitoba, Canada.

Note that the museum is not accessible to people with mobility issues. You need to climb steps to get on and off the boats and navigate a number of other stairs to see all the exhibits. The outside of the ships and the exhibits on the grounds are accessible with level brick walkways.

You can walk the grounds for free, but there is a charge to enter the ships and see the museum exhibits inside the ships. The museum is open during the summer months from the May long weekend to the September long weekend. Check the Marine Museum of Manitoba website for hours and fees.

Never miss a story. Sign up for Destinations Detours and Dreams free monthly e-newsletter and receive behind-the-scenes information and sneak peeks ahead.

PIN IT

Very interesting, Donna. I had no idea that there was such a vibrant shipping history on Lake Winnipeg. I especially enjoyed the cook’s comments.

Linda, the comments from past staff and passengers were one of my favourite parts of the museum.

I can’t imagine how you can cut a ship built in 1897 into sections and then add a section. Sounds crazy. Interesting post, Donna.

Ken, it does sound pretty incredible, doesn’t it. The Marine Museum had a lot of interesting things.

Donna, I’m embarrassed to say I didn’t know about this museum. Sounds like an interesting little tour.

Deb, I was pleasantly surprised with how interesting the museum was. There are actually quite a few very good museums outside of Winnipeg.

Living in Winnipeg, I have visited the Marine Museum several times over the years. I have always enjoyed it and of course there are always changes & improvements. Out-of-town & out-of-country visitors whom we have taken there were impressed with the history.

Eva, the history is indeed interesting. I will keep it in mind next time I am entertaining out-of-town visitors.

The boat on the Keenora, was a lifeboat, not a canoe, its says its a canoe,

Darlene, thanks for the clarification. I’ve updated the post.