Manitoba Russian Mennonite History at the Mennonite Heritage Village

A museum and recreated street village in Steinbach, Manitoba tell the story of Manitoba Russian Mennonites

The Mennonite Heritage Village in Steinbach, Manitoba, 64 kilometres southeast of Winnipeg, tells the story of the Manitoba Russian Mennonites. It is a great place to learn about the Mennonites, their history, and their impact in Manitoba.

The Mennonites are a religious-cultural group established in the 16th century. Russian Mennonites first migrated to the Canadian province of Manitoba in the 1870s and settled in several villages in southern Manitoba where they farmed. Over the years, the villages grew. The Mennonites became involved in politics and opened businesses other than agriculture. Some migrated to the cities. Today, the Mennonite heritage remains strong in southern Manitoba.

In the main entrance building at the Mennonite Heritage Village, museum galleries contain artifacts and historical information. Behind that building lies a recreated Russian Mennonite street village from the late 1800s/early 1900s. Original buildings that have been moved to the site include houses, barns, churches, schools, and businesses. A restaurant serves traditional Mennonite food.

Museum

The museum in the Village Centre building tells the Russian Mennonite story from the 1500s to present-day through a collection of artifacts, old photographs, drawings, maps, and written information.

Mennonites have their roots in the Anabaptism movement that occurred during the 16th century Reformation. In 1536, Menno Simons left the Catholic priesthood to give new direction to the Anabaptist movement in the Netherlands. He emphasized peace, the separation of church and state, and a Bible-based faith and life.

Over time the Mennonites became scattered across Europe as they migrated to escape persecution in search of freedom of religion and the ability to remain pacifists. They developed a unique socio-religious culture. Information and maps in the museum illustrate the extent of the migration, including how they wound up in Poland and Russia. The museum contains information about their life in Russia.

Mennonites from the Netherlands and Germany emigrated to Poland in the 17th century to escape persecution. They were at first exempted from serving in the army. Later they paid a special tax in lieu of military service. The areas along the Vistula where the Mennonites settled in Poland were taken over by Prussia in the late 18th century. Some Mennonites from Prussia began emigrating to Russia in 1788, where they received a Privilegium which included exemption from military service.

There were four main migrations of Mennonites from Russia: to Manitoba and the United States in the 1870s; to Canada and Latin America after World War I; to West Germany, Canada, and Latin America after World War II; and largely to West Germany from 1970 to the early 1990s.

In the 1870s, about 7,000 Russian Mennonites, fearing conscription into military service and state influence on their education system, chose to emigrate to Manitoba because of its fertile, inexpensive land, the possibility of settling in villages, religious freedom, exemption from military service, and the right to control their own schools.

In spring of 1873, before the Mennonites immigrated to Manitoba, the Canadian government set aside eight townships (East Reserve). The poor quality of some of this land led Mennonites to negotiate for an additional 17 townships west of the Red River (West Reserve). Steinbach, where the Mennonite Heritage Village is located, became the commercial centre for the East Reserve.

Both Russia and Canada eventually demanded that Mennonites provide alternative service in exchange for exemption from military service. In Canada, during World War II, about 60% of Mennonite men chose to work in forestry, in hospitals, and on farms. Others entered active military service or the medical corps of the army.

Exhibits in the museum include a variety of information about the lives of Manitoba Mennonites, including village governance, school curriculum, church organization, and daily life.

There are some parallels between the experience of my German ancestors who emigrated to Manitoba from Russia (Russian Poland) in the 1880s and that of the first Russian Mennonites in Manitoba. I grew up in southern Manitoba with Mennonite friends and classmates. I knew a bit of the Mennonite history. Still, I learned a lot at the museum. The information is well-presented and interesting.

Russländer Exhibit

There is space in the Village Centre building for temporary exhibits. When I visited in September 2019, the Russländer exhibit was showing. Russländers were Mennonites who emigrated to Canada from Russia between 1923 and 1930.

The exhibit talked about the so-called “Golden Age” in Russia starting in the late 1880s when Mennonites became more prominent in industry and agriculture, experienced more prosperity (along with a larger divide between rich and poor), and prized higher education. Modernization infused Mennonite life. This came crumbling down when World War I started and continued with the Russian Revolution in 1917. An army led by anarchist revolutionary Nestor Makhno targeted foreign colonists including the Mennonites. They occupied villages, committing acts of robbery, rape, and murder. Highly controversial self-defense units called Selbstschutz established in 1918 divided the community because their actions contradicted the Mennonite beliefs of non-resistance. Combined with the violence were outbreaks of typhus. In 1921, Mennonites were given permission to leave the Soviet Union. Between 1923 and 1927, 24,000 came to Canada.

Life in Canada posed its own challenges with difficulties in finding housing, purchasing farm land, and paying off travel debt. There were tensions with the Mennonites already in Canada, who viewed the Russländers as proud, too enthusiastic about higher education, and too willing to assimilate into mainstream society. The Russländers viewed the Canadian Mennonites as uncultured and unwilling to break with old traditions. The Russländers soon became active participants in Mennonite communities, but the exhibit states that some of these tensions and stereotypes continue to persist between the Mennonite groups.

The Village

The door at the back end of the Village Centre opens into a Mennonite street village from the late 1800s/early 1900s. A collection of original buildings have been moved onto the site to illustrate Manitoba Mennonite life and history. It felt like stepping through a time portal.

The Manitoba Mennonite villages created in the late 1800s followed an age-old European system of farming where fields were arranged in long strips around the villages. Over 50 villages were founded, but by 1923 the open field system had been largely abandoned.

Hochfeld House built in 1877. The log house was an improvement over the sod house.

Hochfeld House built in 1877. The log house was an improvement over the sod house. Housebarn

HousebarnThe farm house with connecting barn was a characteristic feature of Mennonite settlement. The house and barn of the housebarn in the above photograph actually came from two different houses. The Waldheim House with thatched roof was built in 1876 near Morden. The Peters Barn was built in 1885 just south of Mitchell.

Chortitz Housebarn built in 1892

Chortitz Housebarn built in 1892

Looking into the attached barn at the Chortitz House

Looking into the attached barn at the Chortitz House Summer kitchen. Note the painted floor.

Summer kitchen. Note the painted floor. Outdoor clay oven

Outdoor clay oven Garden

Garden Old Colony Worship House was built in 1881. Churches were usually situated in the centre of the village.

Old Colony Worship House was built in 1881. Churches were usually situated in the centre of the village. Plain interior of the Old Colony Worship Centre

Plain interior of the Old Colony Worship Centre Blumenhof Mennonite School, built in 1885

Blumenhof Mennonite School, built in 1885Most Mennonite schools before 1910 had the same basic plan as the Blumenof Mennonite School in the Village with classroom and teacher residence under one roof. There were doors on each side of the school providing separate entrances for boy and girls. Boys sat on one side of the classroom; girls on the other. Instruction in Mennonite schools was initially in German. Eventually most schools included some English instruction.

After World War I, Manitoba and Saskatchewan closed all private Mennonite elementary schools. Those who refused to accept public schools emigrated to Mexico and Paraguay during the 1920s. The public schools allowed German instruction at beginning or end of day. In 1980 bilingual German instruction was reintroduced. Today, there are a number of private Mennonite elementary schools, high schools, and colleges in Manitoba.

The General Store contains a collection of old artifacts as well as a good selection of local crafts for sale

The General Store contains a collection of old artifacts as well as a good selection of local crafts for sale Printing equipment

Printing equipmentThere are several monuments and memorials throughout the Village. There are also collections of old machinery and vehicles.

Side note: Neubergthal, Manitoba in what was the West Reserve is a National Historic Site because it is one of the best-preserved Mennonite street villages in the world. About 120 people still live in that village. You can make arrangements for tours in the summer months. Read about my visit to Neubergthal here.

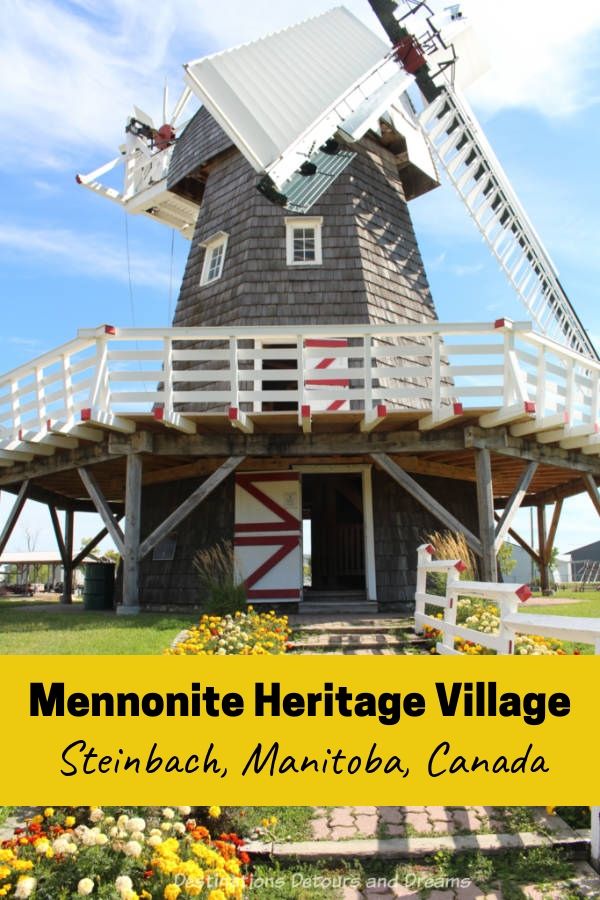

The Windmill

Mennonites used windmills to grind grains and drain marshes throughout their history in Europe and Russia. The first windmill in Manitoba was built in 1877. A replica was built at the museum in 1972. That replica was destroyed by fire in 2000. The current fully functional windmill was rebuilt in 2001 by Dutch millwrights and local tradespeople.

You can go inside the windmill and see its workings. There are two grinding stones. The mill is used to grind flour.

The Restaurant

The Livery Barn Restaurant serves traditional Mennonite food. A sign inside the museum says “Most Mennonite recipes are adaptations of Polish, Ukrainian and German recipes modified over the years to appeal to Mennonite tastes.”

Food available in the restaurant includes foarma worscht, kielke, komst borscht, plautz, plueme moos, and vereniki. Foarma Worscht, otherwise known as farmer’s sausage, is a locally made lightly seasoned smoked pork sausage. Kielke are home-made egg noodles. Komst borscht is a hearty meat broth with cabbage, onions, and potatoes flavoured with dill. Plautz is a cake-like dessert with a crust, fruit filling, and a crumb or streusel topping. Vereniki are boiled pockets of dough filled with cottage cheese. They would be known as perogies in the Ukraine or Poland. Vereniki are often served with Schmauntfatt, a cream gravy. Kielke may also be served with the cream gravy. Bread made from stone-ground wheat milled at the museum accompanies many of the plates.

Visiting The Mennonite Heritage Village

The Village Centre and museum galleries are open year-round with the exception of a couple of weeks closure over the Christmas/New Year period. The village is open May through September. Days and hours vary seasonally. Check the Mennonite Heritage Village website for details.

You can go through the museum galleries before or after walking through the village, but I would recommend going through the museum first. As well as being interesting on its own, the information provides good background and context with which to tour the village. Make sure you pick up a site guide at the visitor’s desk. Not because you’re likely to get lost in the village, but because the guide provides interesting information about the various sites in the village including original building dates, locations, and owners. Allow at least two – three hours for your visit, longer if you incorporate lunch.

Steinbach is a fifty-minute drive southeast of Winnipeg.

Never miss a story. Sign up for Destinations Detours and Dreams free monthly e-newsletter and receive behind-the-scenes information and sneak peaks ahead.

PIN IT

I’ve been to the museum several times over the years and always find new things of interest.

Terry, I think that’s the sign of really good museum.

All of North America, with its vast expanses of open land in the 18th and 19th centuries truly offered all of Europe’s persecuted groups a new start in life. I always find it interesting to learn about how these immigrant communities formed and flourished.

Ken, there are a lot of interesting stories – it wasn’t always easy to survive and flourish.