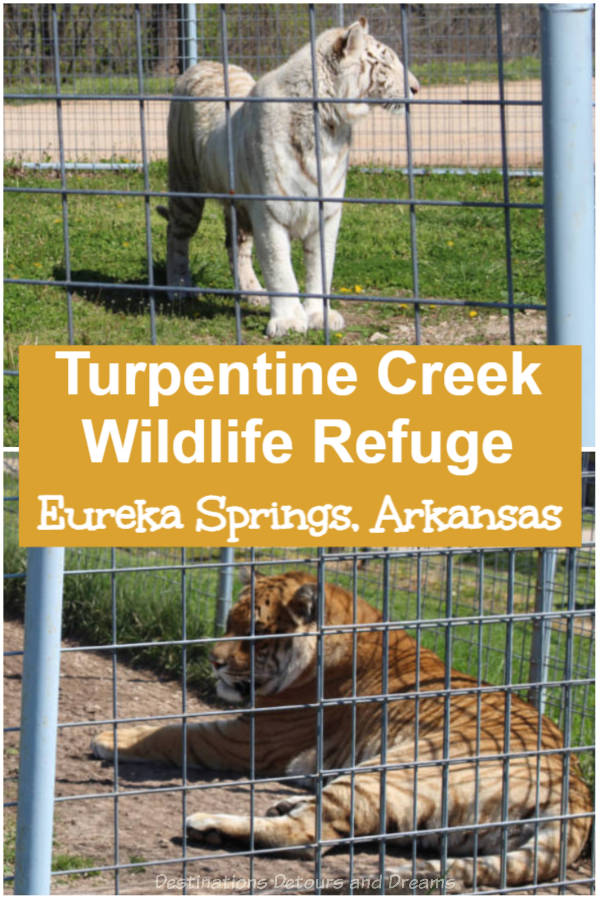

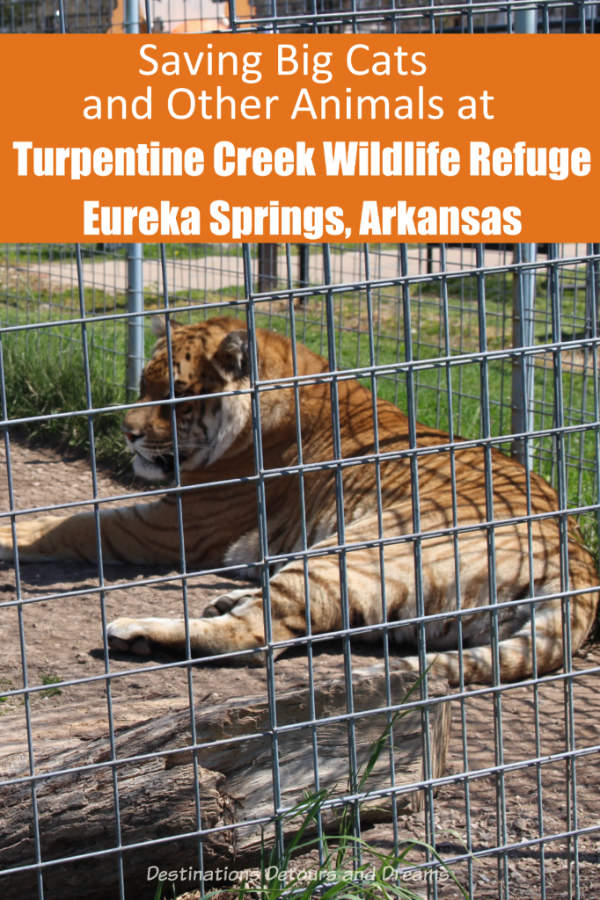

Saving Big Cats and Other Animals at Turpentine Creek Wildlife Refuge

A disturbing and eye-opening visit to Turpentine Creek Wildlife Refuge in Eureka Springs, Arkansas

(Disclosure: I visited Turpentine Creek Wildlife Refuge as part of a post-conference press trip following the 2018 North American Travel Journalists Association conference. Opinions and impressions, as always, are my own.)

Parts of this post may be difficult to read. It was difficult to write. I visited Turpentine Creek Wildlife Refuge just outside Eureka Springs, Arkansas in April and put off writing about the experience until October. However difficult to write or read about, the work Turpentine Creek does to provide refuge for abandoned, abused and neglected big cats, to educate the public, and to advocate for better laws is important.

One of the sanctuary’s biologist/zoologist interns gave me and a group of fellow travel journalists a guided tour of the large cats’ habitat. The sanctuary runs a post-graduate internship program for students with degrees in zoology, biology, animal psychology, veterinary science and other animal-related areas. During their six-month term, students are provided with housing and a small stipend. They work six days a week. The program is highly respected. Over 100 students apply for the 18 positions available each term. The intern acting as our guide said she felt very lucky to be doing her second internship with the sanctuary. The stories she told as we walked through the site were heartbreaking.

Turpentine Creek Wildlife Refuge provides lifetime refuge for abandoned, abused and neglected big cats with a special emphasis on tigers, lions, leopards and cougars. Some had once been pets people had bought as cubs when they were small and appeared cuddly and manageable. But as the intern pointed out, wild animals are wild animals. As the animals grew, they became more aggressive and harder for the owners to manage. Sometimes they were locked in basements or sheds and otherwise abused.

There were a few white tigers at the refuge. White tigers are not albinos as some people believe. The whiteness is the result of a double recessive gene. At the time I visited the sanctuary, none of 3,800 tigers left in the wild were white. White tigers exist in captivity because people think they’re pretty. In the 1950s, a man in India found a male white tiger and bred it with its daughter to create more white tigers. The white tigers alive today are the result of severe inbreeding. That inbreeding creates so many health problems that only 1 in 30 survive.

Note that today, according to the World Wildlife Federation, there are about 5,600 tigers living in the wild. Thanks to conservation efforts, the wild tiger population has increased over the past decade and a bit for the first time in over a century. Threats still exist, however, and wild tigers remain on the brink of extinction. Just over a century ago, 100,000 wild tigers roamed through Asia.

One white tiger at the refuge had been rescued at the age of five. She’d been used for breeding in a manner similar to those of puppy mills and had a cub every four months, which is the length of a tiger pregnancy. In the wild, she would have had a cub every two to three years.

It’s not just white tigers that are bred like this. Other types of tigers and other big cats are bred to get cubs for facilities where you pay to hold or interact with them. The cubs in these facilities are 8 to 12 weeks ago. USDA guidelines do not allow cubs to interact with humans after 12 weeks of age. Where do the cubs go after that? Most go to roadside zoos, circuses and hunting facilities. Very few wind up in sanctuaries like Turpentine Creek. Some of the cubs that have come into the sanctuary’s care after those 12 weeks could not walk because they had so many broken bones from all the handling.

Rescue animals are examined by veterinarians at their original location before being transported to Turpentine Creek Wildlife Refuge in order to ensure they are healthy enough for travel. Once at the Refuge, the animals are evaluated by the facility’s own veterinarian and provided with whatever medical care is necessary. They are quarantined for a period of weeks and sometimes months before animals are housed with each other. Cages and habitats are cleaned daily. Animals are regularly checked for impending health problems. Enrichment activities are used to improve quality of life and provide a diversity of activity to prevent boredom and enable animals to do activities they would have experienced in the wild. A behavioural management program uses a bridge (high-pitched whistle) and reward (food) training method to reduce animal stress and allow staff to address health issues or perform medical check-ups without the use of sedatives.

Exotic pet ownership is poorly regulated. The intern said there are few laws in the United States and they vary from state to state. In 2005, Arkansas passed a law banning the private ownership of large carnivores. The law came about because of lobbying by Turpentine Creek interns following an incident with a rescued tiger. Its owner had decided to let the tiger loose in the Ozarks woods sixty miles from his home. The tiger was missing for four days and made its way back to the owner’s front doorstep. The owner then contacted Turpentine Creek.

The intern didn’t know what the regulations were in Canada, my home. When I checked into it, it didn’t take me long to discover the situation is much the same. There are few regulations and laws vary by province.

Exotic pets cannot be returned to the wild for a variety of reasons. They may have been declawed or defanged. Declawing big cats leads to lameness and limping because of unnatural pressure placed on pads as cats shift their weight to the back portion of their feet to avoid the pain. The abnormal posture also leads to arthritis and back problems. They may be habituated to humans and have developed no hunting or other necessary survival skills.

What can we do about the situation? The most obvious answer is not to take these animals into our homes as pets. Beyond that, we can refuse to patronize the roadside zoos where animals suffer and the facilities offering petting and other interactions.

Be aware that just because a facility has the word sanctuary in its name doesn’t mean it is a true sanctuary. On their website, Turpentine Creek Wildlife Refuge provides guidance as to how you can recognize a true sanctuary. Sanctuaries are non-profit organizations. They are rescue facilities and do not breed animals. They will not allow public interaction with cubs. They do not sell animal parts and they don’t exhibit animals at shows. Animals have access to shade, water and a place to get out of public view. The Turpentine Creek Wildlife Refuge is accredited by the Global Federations of Animals Sanctuaries, an accreditation that means it upholds the highest standards of animal care and safety.

What about zoos? In separating “good” zoos from “bad” zoos, look for accreditation from organizations such as Canada’s Accredited Zoos and Aquariums and the Association of Zoos and Aquariums to ensure the facility treats its animals safely and humanely. I do wonder whether even “good” zoos should exist, although I know many do important work in research, education and saving animals from extinction. Should any wild animal be caged solely because of our human fascination with the animals? I have mixed feelings. Zoos don’t generally top my list of things to see when I travel but I do visit zoos from time to time and I will not be completely boycotting zoos in the future. I will, however, be selective, look for accreditation, and visit with a more critical eye.

A visit to a true animal sanctuary is an interesting and eye-opening experience. Turpentine Creek Wildlife Refuge is open daily year-round with the exception of Thanksgiving Day, Christmas Eve, and Christmas Day. The big cat habitat area is viewable only via guided tours led by one of the interns. There are also a few suites and one RV/tent site that can be rented.

Never miss a story. Sign up for Destinations Detours and Dreams free monthly e-newsletter and receive behind-the-scenes information and sneak peeks ahead.

PIN IT

I’m sure there are some really sad stories that go along with the animals there. Hard to understand why anyone would think it is okay to take a tiger into their home as a pet.

Ken, you do have to wonder what they were thinking.