Bison Safari on the Canadian Prairie

A bison safari adventure at FortWhyte Alive in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

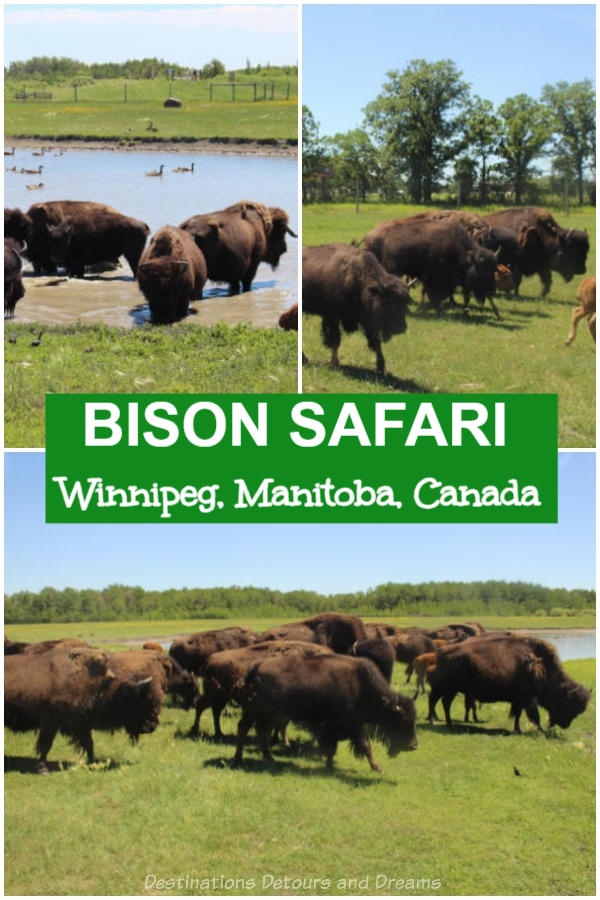

I would never have predicted my first safari would take place in my home town on the Canadian prairie. As the bus pulled up alongside a herd of bison at the edge of a pond in a grassy field, I and seventeen other safari guests looked out the windows and aimed our cameras. Up close to North America’s largest land mammals, I was struck by their majesty and power. Although I saw the edges of the city around me, I felt as if I was in the middle of prairie wilderness.

FortWhyte Alive is a nature preserve, park and recreation centre in southeast Winnipeg, Manitoba. They keep a small herd (around 30) of bison. The herd of bison is sometimes visible in the distance from a viewing station on one of their trails, but the best bet to see them up close is on one of their bison safari tours.

Before we boarded the bus and during the ride across the field toward the bison, the guides provided information about bison in general and more specifics about the FortWhyte Alive herd.

The correct term for these beasts is bison. Buffalo refers to a different kind of animal, but the term buffalo has been so widely used in North American most people understand what is meant when the word is used. Bison have a distinct hump on the back. Both males and females have horns. Adults measure 5 to 6 1/2 feet tall at the shoulders. Females weigh 790 to 1200 pounds, males 990 to 2200. Their tails talk. If the tail swishes side to side the bison is content (or swatting bugs). If the tail curves in a u-shape the bison is disturbed (or pooping). The nose is the bison’s sharpest sense. Hearing is also acute. Their sight is, however, not so good. The can detect motion up to five miles away, but are not good with stationary objects.

Bison are herbivores. They eat grasses (and they poop a lot). Recent studies have shown that grazing by bison increases the diversity of plant species in tall-grass prairie. In the winter they swing their heads side to side to push away the snow to find grass underneath.

The “wild” herd at FortWhyte Alive live in large fenced grass fields, where they generally fend for themselves with a little bit of help from FortWhyte Alive. They are moved, roughly on a monthly basis, between two fields so they have fresh grass to eat. There is a spray station the bison can go under to help get the bugs off. Staff leave out a salt lick and put hay out during the winter months.

It was a hot day in late June when I visited. Some bison waded in the pond to cool off. A couple rolled in the dirt. They do this to deter biting flies and help shed fur. The bison were in the midst of losing their winter coat. There are no particular shelters for the herd. Bison won’t go under shelters or indoors. Temperatures become difficult for them only when they get below -40 Celsius (also -40 Fahrenheit) or above +40 Celsius (104 Fahrenheit).

There were some newer additions to the herd, calves born in spring. Calves are able to stand and nurse within 30 minutes after being born and can walk in a few hours. The hump and horns begin to develop at age 2 months and they are weaned at about 5 months. The light-coloured calves darken as they age.

The largest bison in the herd is the alpha male. FortWhyte Alive keeps only one adult male in the herd. When male calves reach a certain age, they are given to ranches. Adult males would fight each other for dominance. The primary role of the male is for breeding and protection.

The current alpha male at FortWhyte Alive is two-year-old Charles III. His father and grandfather were the previous alpha males. Charles II choked on something he ate and died after three years. Charles I was with the herd for about twelve years when he developed kidney issues. Staff had decided the humane thing to do would be to put him down, but two days before that was scheduled to happen he laid down and died. Bison can live up to twenty years in the wild.

As we watched the bison around the pond, they started to move as a group. Our guides were surprised to find them this active on a hot day. The herd is led by a lead female. It is she who determines when and where they move. Watching them move across the field gave me a glimpse into what it must have like centuries ago when thousands of bison roamed the prairie. I could imagine the roar of their hooves and the earth shaking beneath them. You can watch them on the move in the short video below.

Indigenous peoples hunted bison. They dried the meat to create pemmican, carved bones to create knives or boiled them to make glue, created cups from horns and hooves, and used the skins for clothes, moccasins, and blankets. The “buffalo coat” was once a standard part of the Winnipeg Police force’s winter wear. One of our safari guides related how one former officer told him he never thought twice about dealing with a knife situation when wearing the coat.The knife would not get through the coat.

Wild bison in North America once numbered 60 million. Over-hunting and habitat loss decreased their population to approximately 500 by 1900. Conservationists helped protect the remaining animals and their population grew rapidly.

As we watched the bison lumber lethargically through the field, they suddenly broke into a run and stampeded toward the edge of the field. One of the guides,who has been doing these safaris for about 14 years, says he’d never seen anything like it. Bison can run over 60 kilometres (40 miles) an hour. It was both impressive and a bit terrifying to watch. They stopped suddenly when they reached the locked gate into the next field and slowly turned around and ambled away.

The guide pointed to the flattening cumulus clouds in the skies and suggested that perhaps the bison sensed a storm coming. Bison are frightened of thunderstorms. The guide noted that helicopters also scare them, but the airplanes that fly over (the field is under a flight path) don’t seem to bother them.

That night, as thunderstorms woke me at four a.m., I remembered the bison stampede. After that bison safari, I think I will often see bison thundering in my mind’s eye as I look across open prairie.

FortWhyte Alive one-hour-long bison safaris operate from May through September. You never exit the bus, but large windows on either side allow for great views. When we stopped by the herd at the pond, the driver opened the door for a short while so people who wished to get photos without a glass barrier had opportunity to so from the steps inside the bus. The bus parks near the herd and after a while will turn around to give the other side of the bus the better view. The bus follows the herd if it moves.

The Bison Safari is one of the places featured in my guide book 111 Places in Winnipeg That You Must Not Miss.

Never miss a story. Sign up for Destinations Detours and Dreams free monthly e-newsletter and receive behind-the-scenes information and sneak peaks ahead.

PIN IT

I couple of weeks ago I was in Montana watching the bison in Yellowstone National Park. Fascinating to see, especially since it was mating season. Lots of posturing going on among the males like flopping around on the ground kicking up a dust storm. What female bison could resist that?

Ken, It would be interesting to see that posturing. It makes me wonder what different behaviour I might observe if I took the bison safari later in the summer.

Thanks, Donna. I read this with great interest because it said everything I had previously wondered about bisons. Again, you had all the detailed answers! Probably, visiting in September is better so they are ready with their winter coat?

Carol, I’m glad I was able to provide answers to some of your questions. I’m not sure when the bison get their winter coat, but I think that by the end of July all the shedding would be over. The bison might act a bit differently based on the time of year (and temperature). Later summer is mating season and there may be different behaviours because of that.

I would have never thought of a safari in Winnipeg, Canada. Since we will be traveling in Canada next summer, it is something to consider in our itinerary.

I never realized that Bison are herbivores. The video has me feel like I am there. Seeing the Bison stampede must have been quite a sight.

Wendy, you might want to consider Fort Whyte’s A Prairie Legacy: The Bison and Its People tour. It is a 3 hour tour that includes the safari followed by a chance to power a voyageur canoe, explore a tipi and a pioneer sod house, and end with wild bush tea and bannock over a campfire. That tour is a Canadian Tourism Signature Experience, an experience Canada Tourism has designated a once-in-a-lifetime travel experience. I’m not comfortable on the water and so opted to just do the safari.

Hi Donna. Thx for the great post. I learned a lot about the bison from it. I’ve not been to Fort Whyte since the days when they called it Fort Whyte Centre. A very long time ago. I’ll make an effort to get back there soon.

Doreen, I went to Fort Whyte Centre a fair bit when my daughter and step-daughter were little, but then didn’t go for a lot of years. I found quite a few changes (expansions) among the familiar when I returned a few years ago. I think you’d enjoy visiting again now.

Fun! I was expecting these bison were further west. Now I know I can visit them in Manitoba.

Kristin, it was an interesting tour

Thanks for this post Donna! Intersting to learn that the herd is led by a lead female who determines when and where they move. You are lucky to have discovered them on home ground.

Bola, I didn’t know much about herd dynamics before taking this tour and also found the bit about being led by a female interesting.

I’ve been fortunate to see bison a few times, such as at Yellowstone Nat’l Park — always amazing to see them grazing in the fields. But you really got up close! What a great experience. Interesting information about them, too.

Cathy, I certainly found the information interesting. There was a lot I didn’t know about bison. I’ve seen photos of the bison in Yellowstone. It would amazing to see them grazing in real life.