Crystal Bridges Museum Where Art and Ozark Natural Beauty Intersect

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas marries art and architecture with nature

(Disclosure: I visited the museum as part of a post-conference press trip following the 2018 North American Travel Journalists Association conference in Branson, Missouri. Opinions and impressions, as always, are my own.)

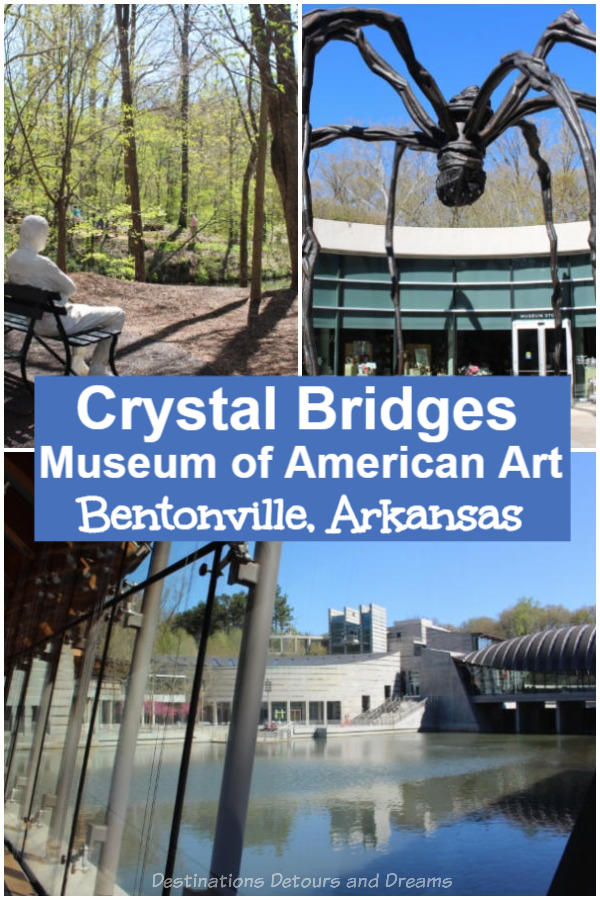

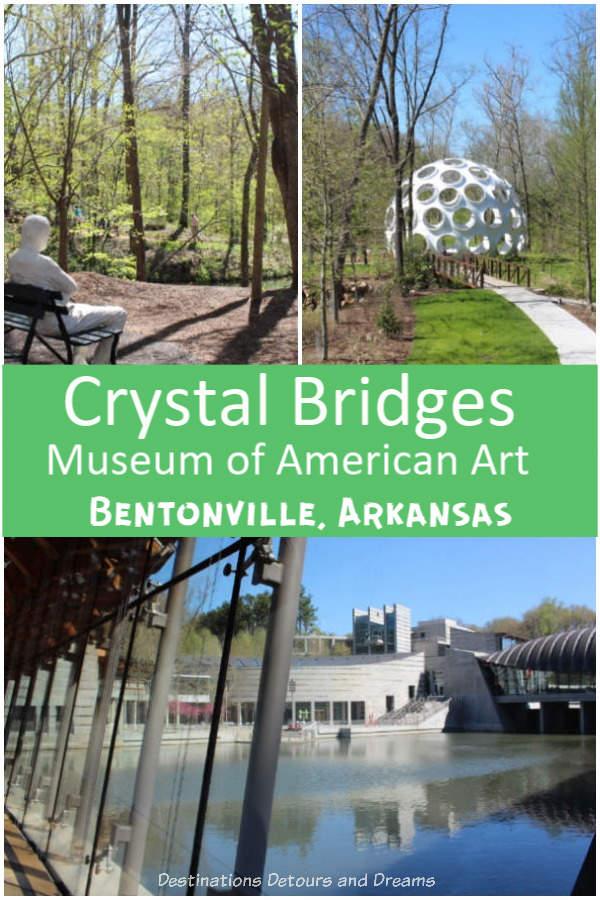

No large towering building greeted me when we pulled up in front of the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas. Instead, I looked down into a vista where the building meandered through and blended into the hills and forest of the Ozark countryside. The entrance itself reminded me of an entrance to a train or subway station and in a way that is what it was. The museum building rests in a ravine. We took an elevator down to a courtyard leading into the entrance lobby.

The museum was established by Alice Walton, daughter of Walmart founder Sam Walton. She had a life-long interest in art and discovered that her study of American art enhanced her appreciation of American history. A desire to make great art accessible to the people in the area she loved and called home led to the creation of the museum.

The museum sits on 120 acres of Ozarks forest, much of which belonged originally to the Walton family. Alice and her brothers played here as children. Alice wanted to maintain the land’s natural beauty. Architect Moshe Safdie incorporated landscape into the design. Museum staff often say the building is the museum’s largest exhibit. It is built around ponds created by damming the stream running through the ravine. The building’s curves mimic the hillside and rolling landscape. The materials chosen for the construction of the building are intended to weather over time helping the museum blend into its surroundings.

The galleries are actually a series of connected buildings. Floor to ceiling windows along passageways allow light in and offer views of the ponds. Curved exterior walls in galleries create a feeling of flowing through the building while offering unique positioning for viewing the works of art.

The galleries are organized by time period from early American through to present day. Yet the arrangement of pieces within those galleries is somewhat eclectic. In the Early American gallery, modern pieces are deliberately placed beside older pieces to provide a contrast.

A painting of George Washington by Charles Willson Peale (circa 1779-81) sits beside the Johnny by Susie J. Lee (circa 2013). Johnny is a high-definition video portrait of a worker in the oil and gas industry. It is a compelling picture. Johnny’s eyes seemed to follow me through the gallery.

Writing on the wall in the Early American Gallery highlights key elements of American history reflected in the artwork.

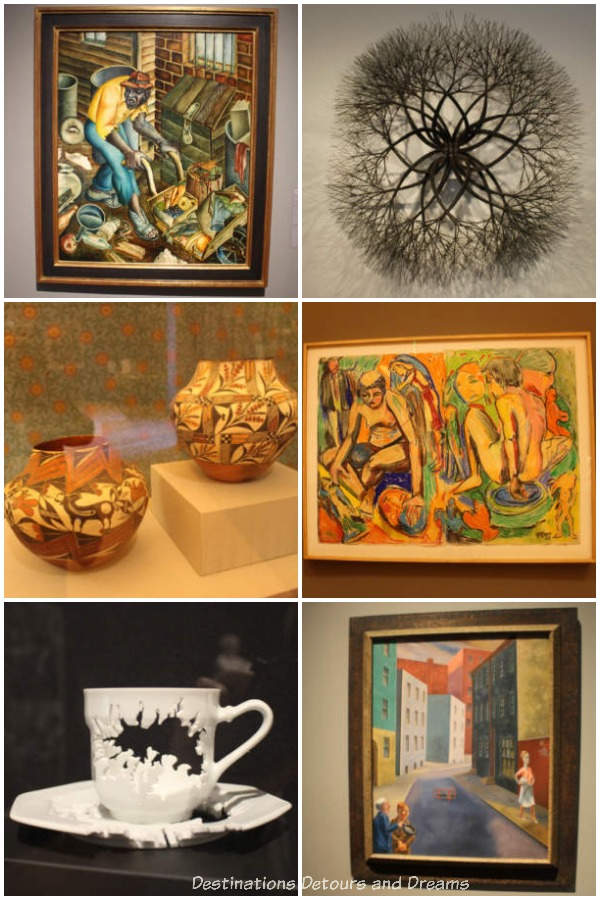

Art featured in the above photo:

Top Row: “The Garbage Man” (oil on panel) by John Asana Thomas Biggers;

Untitled (bronze wire) by Ruth Asawa

Middle Row: Jars (clay and pigment) by Acoma artist;

“World Civilization: Reflective” (pastel on paper) by Viola Frey

Bottom Row: “Sommerfarm” (hand-cut bone china) by Elizabeth Alexander;

“The Gallants” (oil on fiberboard) by Osvaldo Louis Guglielmi

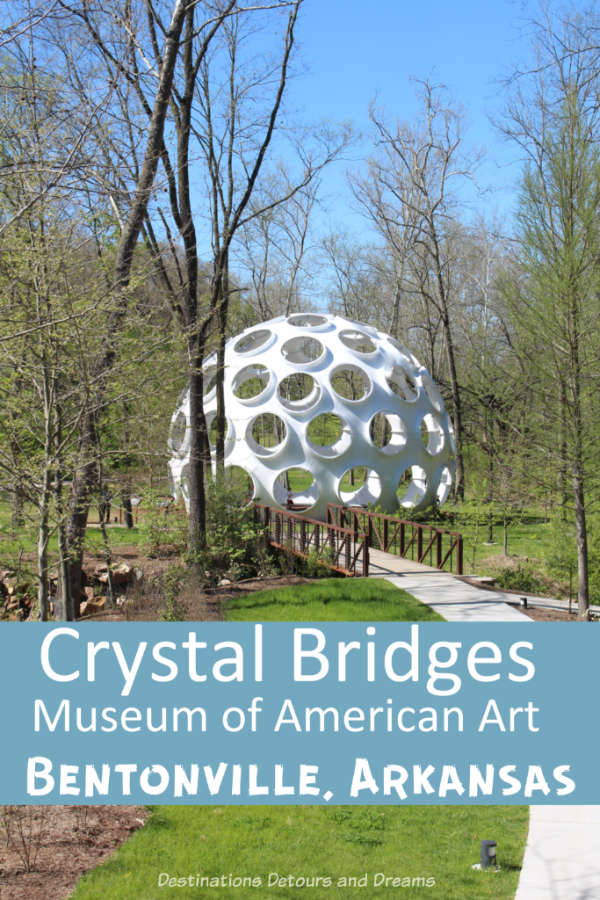

The art continues outside along an art trail featuring a variety of sculptures, native plants and waterways. There are also several hiking trails of varying length and degrees of difficulty.

The museum building is not the only piece of architecture on the property. The Bachman-Wilson House on South Lawn is an example of Frank Lloyd Wright’s “Usonian” style, the residential architectural style he developed during the Great Depression to create simpler, lower-cost houses designed to be within reach of the average middle-class American family without sacrificing quality. The house was originally built for Gloria and Abraham Wilson in 1956 in New Jersey. Crystal Bridges acquired the house in 2013 and with the help of the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy deconstructed, moved and reconstructed it.

The interior of the house is open to the public, but no photos are allowed. You can get a set of headphones to provide audio information about the rooms and their design.

Although the way art, architecture and nature are combined at Crystal Bridges creates a sense of calm and peace, I found myself somewhat overwhelmed at first. I wasn’t sure where to focus my attention. I suggest you allow ample to time in your visit to appreciate all of it.

Admission to the grounds and the museum’s permanent collection is free. There is a charge to see temporary exhibits. Entrance to the Frank Lloyd Wright house is free, but you must get a ticket for a specific time at Guest Services. There is limited space inside the house and the number of people entering at one time is controlled.

Never miss a story. Sign up for Destinations Detours and Dreams free monthly e-newsletter and receive behind-the-scenes information and sneak peaks ahead.

PIN IT

What an interesting setting: in a ravine! Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art may not look like much from the outside, but the collection of artwork it holds inside is quite impressive. That quirky coffee cup is adorable!

The outside of the museum is actually quite impressive once you get into the ravine. You just don’t see it when you first pull up. It has a very interesting collection of art.

Lots of interesting stuff and it looks like they have a great space to display it. I also found “Johnny” to be riveting even from just this photo.

Ken, I think I missed a lot in the gallery because I was so mesmerized by Johnny’s eyes following me.

The two men side by side really is compelling–what an interesting approach to hanging art. I’ve always wanted to go to the Ozarks–another place on the travel list. Reading about the Frank Lloyd Wright house being transported reminds me that a summer trip to Falling Water is also on the list. It’s only an hour away!

RoseMary, I was impressed with my short visit to the Ozarks. And I’d love to see Falling Water. I hope you do go soon so I can read all about it.