New Iceland Heritage Museum: Icelandic Roots in Manitoba

The New Iceland Heritage Museum in Gimli, Manitoba tells the story of Icelandic settlement in an area of Canada that came to be known as New Iceland

Gimli, Manitoba is located on the western shores of Lake Winnipeg about an hour’s drive north of the city of Winnipeg. The town, whose name means paradise in Icelandic, is in the centre of an area once known as New Iceland. The New Iceland Heritage Museum in Gimli tells the story of New Iceland and the Icelandic experience in North America.

Between 1870 and 1915, almost twenty thousand Icelanders left their country in search of a new home, driven by a string of long hardships, which included extreme cold, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, destruction of the sheep industry, and a measles outbreak. In 1875 the eruption of Mount Askja blanketed the East Fjords with volcanic ash. It wrecked the island’s economy and was the last straw for many Icelanders. In the years following, up to 20% of the island’s population emigrated, mostly to Canada and the United States.

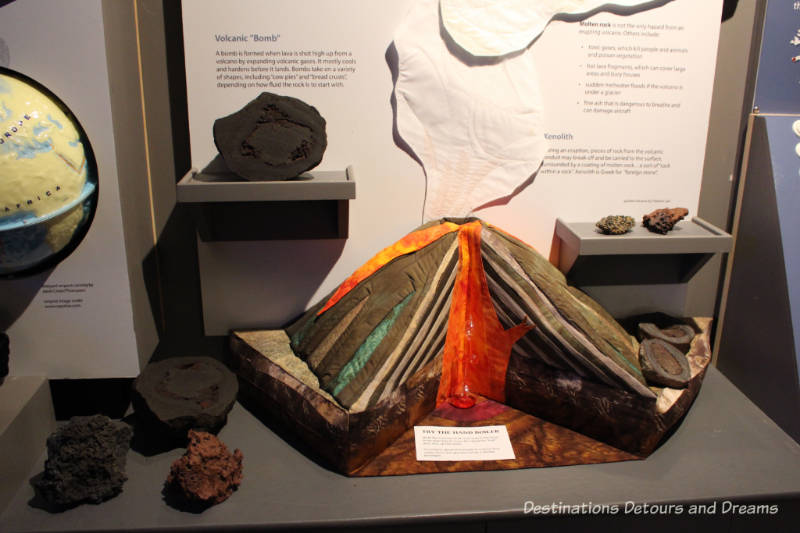

My visit through the Museum started in a small room focused on the physical geography of Iceland: its hot springs which provide geothermal energy and its volcanic activity. There is information on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and famous Icelandic volcanoes. You can enter a ballot to guess which volcano will be the next to erupt.

While the people of Iceland were struggling in the late 1800s, the governments of Canada and the United States were looking for farmers to settle the west. Both countries offered immigrants free land. In Canada, an Act of Parliament in 1871 set up immigration districts and agencies. Immigration Aid Societies were formed. A few of the first Icelandic immigrants were hired to return to Iceland and encourage people to move to Canada. Sigtryggur Jonasson was one of these. He wrote a pamphlet “New Iceland in Canada” and became instrumental in establishing an Icelandic settlement in Manitoba.

In 1875, the Canadian government granted Icelandic immigrants a reserve region along the west shore of Lake Winnipeg. Here the immigrants established Nýja Ísland or New Iceland with a constitution of its own. New Iceland became part of the province of Manitoba in 1881, but retained its own system of government until 1887.

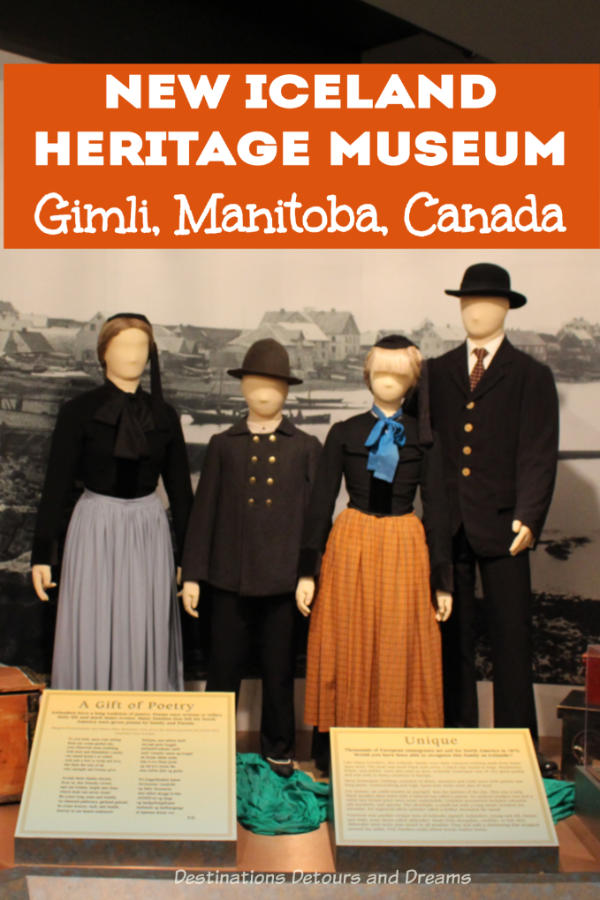

The arriving Icelanders wore homespun wool clothing. Sorta, which was a black clay found in bogs, blueberries, lichen, and nettles were used as dyes. The women wore small hats with long tassels. Footwear was made of sheepskin, cow hide or fish skin, and was tied with a drawstring at the ankle.

They brought with them values of law, literacy, democracy, religious faith and love for the Motherland. And a few personal possessions. Packing suggestions made by Björn Andrésson in a letter back home in 1877 included warm woolen clothing and bedclothes, tools, as much rope as possible, spinning wheels and carding combs, and good chests. He suggested whey, dried fish and smoked meat as foods that would last. He recommended English gold, not Danish, because of its exchange rate. He said chewing tobacco was unobtainable in the New World except for a horribly sweet kind. Most people turned to smoking. He did not need to tell people to bring books. Every family brought as many books as possible.

Life in the New World was hard. The Icelanders were not prepared for the harsh winters. In 1876 a smallpox epidemic took a heavy toll. They had been fishermen in Iceland but Lake Winnipeg froze over in the winter. The flora and fauna were different than they were used. They struggled hunting for food. Rabbits were unknown in Iceland. They were reluctant to eat them because of their similarity to cats. Eventually they adapted, through perseverance and assistance from the natives, who showed them how to set fishing nets under thick ice.

Many of the pioneers were devout Lutherans. Prized possessions included religious books. Formal congregations were established throughout New Iceland, but ministerial visits were irregular due to distances and poor roads. Religious strife arose in 1878 when two pastors offered different versions of Lutheranism. In 1879, many settlers followed the more conservative pastor to Dakota Territory.

In 1897, the New Iceland reserve was opened to settlement by non-Icelanders. The first to come were Ukrainian homesteaders following by Polish and Hungarian settlers. By 1917, the area no longer had an exclusively Icelandic characters, although the Icelandic heritage would remain strong for another century.

The last section I toured in the Museum was again focused on physical geography, specifically rocks. Iceland was said to be young as its rocks are little more than 20 million years old. Manitoba is old with rocks over billions of years old. Mixed in with rock information in this room were bits of Icelandic lore and mythology: “hidden people”, trolls, and magic stones.

The New Iceland Heritage Museum in Gimli is open daily year-round from 10 am to 4 pm. It provides an interesting look at Icelandic immigration, the life of early settlers, and overall history of the area. When I visited, the couple ahead of me was from Iceland and the Museum was getting ready to host a tour group from Iceland. That number of Icelandic visitors may not be a daily occurrence, but it highlights the ongoing connection this area has with Iceland.

Never miss a story. Sign up for Destinations Detours and Dreams monthly e-newsletter and receive behind-the-scenes information and sneak peaks ahead.

PIN IT

Once again, Donna, you’ve done an excellent job in encapsulating what a visitor will see at an attraction. I’ve been to the NIHM many times, but did not notice all the things you have mentioned. So thanks for that, and for helping spread the word about this great Interlake attraction.

Thanks Doreen. I often find that when I visit a museum a second or third time, I notice something I missed the times before.

It’s always fascinating to see where different groups of immigrants end up. When you first hear that there is an Icelandic community in Manitoba it kind of leaves you scratching your head. But when you hear The whole story it all makes sense.

Ken,it is fascinating to see where immigrants end up and how and why they got there. Often, they’ve followed other family or countrymen to a particular place.

Nor would I want to have to use a yoke to carry my water, Donna. Yikes to the very notion. I find it interesting that they felt the winters were hard, given that they came from Iceland. It’s all in our perspectives, isn’t it?

RoseMary, It is all in perspective, but I have no doubt those winters were very harsh!

What a fascinating piece of history. I hadn’t heard of New Iceland and I had no idea that so many Icelanders has emigrated. That museum really seems to bring it all to life.

Karen, the museum does a good job of bringing it to life.

Thanks for the intro to the New Iceland Heritage Museum and another chapter in Canadian history, Donna. Unless we’re Native Americans, all of us from North America are descendants from immigrants and I find the stories of the early immigrants to be fascinating as I imagine setting off on to a new country with so many uncertainties. In the case of the Icelander immigrants, they may have chosen Canada driven by desperation but it seems to me that they would also have had a great deal of fortitude, optimism and creativity to set off for a new life in an unsettled land! Anita

Anita, it must have taken a great deal of fortitude, optimism, creativity and strength to settle in a new land with such uncertainty. I find it hard to imagine. Similarly the struggles and strength needed by today’s refugees is hard to fully comprehend from the comfort of my own life.

Some interesting facts here! We visited Gimli many times when we lived in Winnipeg but I didn’t know much about the history. I had no idea New Iceland had its own constitution!

Michele, I knew a little bit about New Iceland history, but didn’t know it had its own constitution until I visited the museum.

This is really cool. I love museums like this, ones that tell a very specific story.

Thanks Renada.

It is great to learn more about Icelandic influence in this part of Canada (had no idea). I enjoy places were there is big influence from other countries and you can enjoy a bit of that country even if it is far. Is there Icelandic influence on the area?

Ruth, you ask a good question about Icelandic influence on the area that I don’t know how to answer. There are many Icelandic place names. Many Lutheran churches in the area were started by Icelandic immigrants. The University of Manitoba has an Icelandic studies program and there is an Icelandic club. Beyond that, I think the influence is less noticeable, although how values and culture have shaped the generations who know claim at least some Icelandic heritage is hard to define.

Having visited Iceland last year, it is hard to imagine that they managed to move to a place with even harsher conditions than those they left—-minus the volcanic eruptions and earthquakes. It is true that because of the Gulf Stream and all the geothermal activity, Iceland is warmer than one would imagine from the name, but it is a bleak, windswept place with very few trees.

When you think that there was discord among Lutherans over doctrine, it helps explain the Sunni-Shia rift that so many Westerners claim to find baffling.

Suzanne, the subtleties of doctrine dispute can be baffling in many religions. Harsh as conditions in New Iceland were, they stayed and more came, so perhaps it still offered a better life and future.

I didn’t know about the Icelanders of Manitoba, but it makes me think of the immigration of my Swedish ancestors to Minnesota. I’m sure their experiences were quite similar. The New Iceland Heritage Museum in Gimli looks like its very well done and has a great many interesting exhibits.

Cathy, I imagine there are many similarities between the immigrant experiences. The Museum is very well done.

You always has such keen eye for detail! I’ve never been to Manitoba, by the immigration experiences are fascinating.

Thanks Patti. The immigrant experiences are fascinating.