Rural Manitoba History at a Multicultural Heritage Village

Arborg and District Multicultural Heritage Village preserves the past of a rural Manitoba farming community

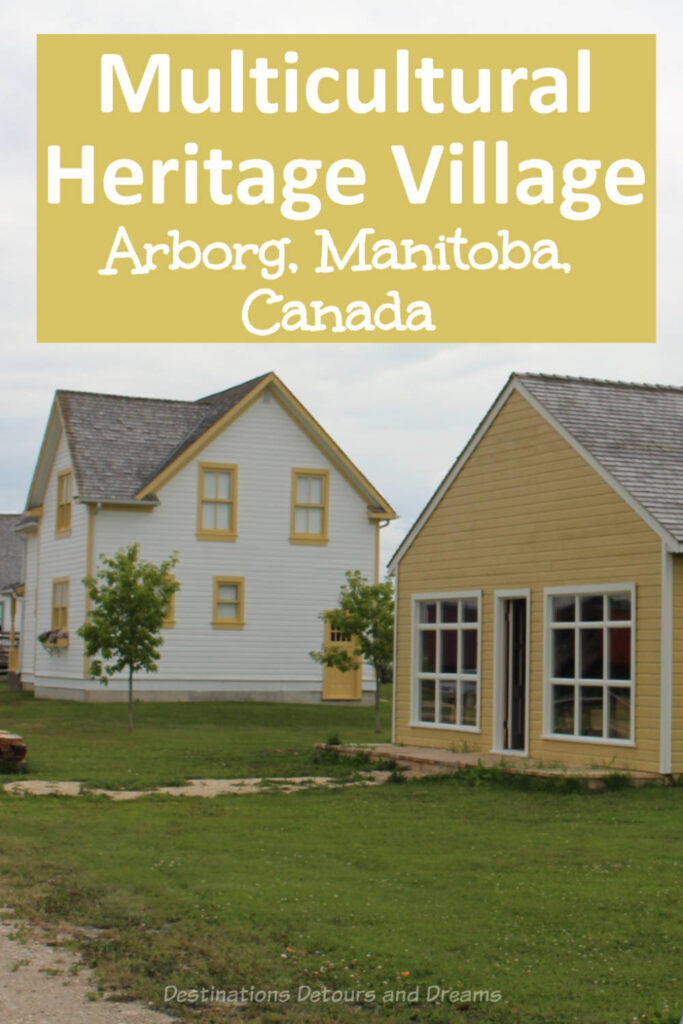

Arborg, 150 kilometres north of Winnipeg, is home to a heritage village interpretative centre showcasing the history of this Manitoba farming community. Arborg and District Mulitcultural Heritage Village was incorporated in 1999. Since then, fourteen historical buildings have been moved to the site and restored to create a village which brings history to life.

Arborg settlers were primarily of Icelandic and Polish-Ukrainian origin. Arborg lies just west of what was once the colony of New Iceland, a reserve along the western shores of Lake Winnipeg granted by the government of Canada to Icelandic immigrants in 1875. Three Borgfjord brothers moved west of New Iceland to the Arborg area just before 1890. Larger scale settlement began in 1900 with Icelanders from North Dakota searching for homesteading land. The community applied for a post office in 1902. The post office was named Ardal (“river dale”) after the postmaster’s homestead.

In 1910, the Canadian Pacific Railway built a line north to Ardal. A town sprang up and was named Arborg, which means “river town” in Icelandic. The rail line opened the area to trade and transportation. Unsettled lands around the town were promoted as homesteading sites. Within a few years, hundreds of Polish and Ukrainian immigrants arrived.

The Arborg and District Multicultural Heritage Village is open to the public during summer months. Tour guides lead visitors through the grounds and into buildings. They provide historical background and insight into daily life within the buildings. My husband and I arrived at the Village at the same time as a bus load of 50 tourists from Iceland. That group was divided into four smaller groups, one of which we joined for a tour through the Village. In preparation for the bus load of tourists, additional interpreters had been stationed in most of the buildings to assist the tour guides.

One of the homes in the village is the Sigvaldason house, which was home to the Sigvaldasons and their 16 children for 50 years. Inside, we get an idea of how the family lived. Many of the artifacts are original to the family.

Life in the new land was hard for the Icelandic immigrants. Before the creation of New Iceland, Sandy Bar, a short distance northeast of Arborg, was home to a small community of Cree and Saulteaux. Despite being displaced by the new arrivals, the Indigenous Peoples helped the Icelandic immigrants adapt, showing them how to construct log cabins, make a boat leak-proof, hunt, and fish through the winter ice. The Icelandic people had been fishermen in their home land, but they were used to catching larger sized fish. The first nets they made had wide holes the fish swam through.

John Ramsay was a Cree hunter whose contributions to the survival of the Icelandic pioneers became legendary. He is credited with saving many lives during the first few difficult winters. A small pox epidemic in 1876 was devastating to both the Icelandic immigrants and the Indigenous population. Ramsay’s wife and three of their four children died. Ramsay buried his wife and children in a cemetery where many other Cree, Saulteaux and Icelandic victims were also buried. Ramsay later purchased a headstone for his wife’s grave and built a picket fence to protect the grave site.

By the the turn of the nineteenth century, the Sandy Bay townsite and cemetery had been abandoned by Icelanders and Indigenous Peoples. Newly arrived Trausti Vigfusson began having dreams in which Ramsay begged him to right his wife’s overturned headstone and replace the fence. Vigfusson had never met Ramsay but knew of his reputation. Despite being poor himself, Vigfusson restored Betsey Ramsay’s grave in 1917. Since then, the grave site has been restored many times and is now a designated heritage site within the Rural Municipality of Bifrost.

Trausti Vigfusson’s log cabin was the first house moved to the Arborg and District Heritage Village. But it was not the first time the cabin had been moved. It has resided in three different communities. An opening in the outer wall reveals Roman numerals on the logs, a numbering system used to put the cabin back together after being moved.

The Slipchuk House was built in the 1920s in Komarno, Manitoba. It illustrates the techniques Ukrainians used to construct their homes and provides a glimpse into the life of early Ukrainian settlers.

A three-sided log hut behind the Slipchuk House contains a Ukrainian outdoor oven. Ukrainian bake ovens were built from natural materials and used all year round. They would not have had a shelter around them. The hut is a Heritage Village addition to protect the oven on display.

The store is the only building in the Village that is a reproduction and not an original building. Several stores had been donated but none were in good enough shape to be moved. The shelving and contents are original to other stores.

Popular Heights School is a large one-room school built in 1918 and used until the 1960s. Inside, we learned how teachers handled different grades within one room from an interpreter who once taught in a one-room school. The Icelandic immigrants placed a high value on literature, literacy and education. Although they may have spoken Icelandic and read Icelandic books at home, they insisted their children learn in English in order to be successful in this new land.

Construction of St. Demetrius Catholic Church in Bjarmi began in 1915 and completed in 1921. Many original artifacts have been maintained inside. After restoration, the church was re-sanctioned so it can still be used as a church. It is booked occasionally for weddings or funerals.

Several of the interpreters in the buildings spoke Icelandic with the tour group from Iceland. (In those cases, our tour guide took my husband and I to the side and gave us information in English.) One of the Icelanders told me the Arborg Icelandic had a North American accent and included a few outdated words in its vocabulary. In spite of that, the interpreters and Icelandic tour group understood each other and seemed to converse easily. The Icelanders all spoke English as well and had no difficulty understanding interpreters when they spoke in English.

There are more buildings and much more to be seen inside than I’ve shown in my photographs. And the Village continues to grow, thanks to the efforts of many dedicated volunteers.

The Arborg and District Heritage Village is open from the May long weekend to the end of August, Monday to Saturday from 10 am to 4 pm and Sunday from noon to 4 pm. A tour typically takes one and a half to two hours. It was well worth our drive from the city.

Never miss a story. Sign up for Destinations Detours and Dreams free monthly e-newsletter and receive behind-the-scenes information and sneak peeks ahead.

PIN IT

Hi Donna, My husband’s sister and her husband live just outside Arborg. We visit them a few times a year and thus have been to Arborg many times over the years As such I am embarrassed to say I have never visited the Heritage Village. After reading your article, I’ll make a point of making time to visit it.

Eva, I think the Heritage Village is worth seeing on one of your visits to Arborg.

How lovely – I would very much enjoy visiting this venue.

Thanks Susan.

An interesting story. I’m just marveling at the fact that a community of Icelandic immigrants grew in rural Manitoba.

Ken, between 1875 and 1915 about one quarter of Iceland left the country because of volcanoes and other disasters. A large number settled in Manitoba. I’ve read that the area of Manitoba once known as New Iceland has the largest ethnic Icelandic population outside of Iceland. Gimli, the town at the heart of the area and about 1/2 hour from Arborg, has an excellent museum called the New iceland Heritage Museum. I will be writing about that museum and a bit more about New Iceland history in a future post.

Fabulous post, Donna! I used to go to Arborg to visit an uncle of mine who was in the personal care home. But since he’s passed on, I haven’t been back. I didn’t know they had this marvellous pioneer village and will try and get there sometime soon.

Doreen, I only learned about the pioneer village last year, towards the end of summer, and decided to try and get there this summer. It is very interesting and quite an accomplishment for a small town.

I had no idea that there was a New Iceland area in Manitoba! What a great way to explore their history and heritage.

Karen, Manitoba was one area Icelanders came to in the late 1800s after volcanoes and other disasters caused hardship at home. The Icelandic roots in the area they settled north of Winnipeg remain strong today.

Every time I visit a place like this, I’m reminded of how difficult life was for early settlers to this part of the country. I think I would have made a terrible pioneer! It’s nice that the village includes a range of housing to show the variety of situations people encountered.

Cindy, I too would have made a terrible pioneer.

What an interesting post. My ancestors were early settlers from Ukraine in rural Saskatchewan and shared many of the hardships the Icelandic did….most notably the brutal winter weather and isolation. The story of John Ramsay and the loss of his family is especially tragic.

Thanks Michele,I think there are likely a lot of similarities among the settlers’ stories, whatever their origins. I always marvel at how they persisted through some of the hardships.

What an enjoyable tour you had–thanks for sharing it with us. This is exactly the kind of tour I would enjoy–history and a mix of people in the tour. Perfect.

Rose Mary, it was an enjoyable tour. I’m glad you liked reading about it. I’m sure you would have enjoyed it in person.

I love these kind of tours Donna and the history of the people who settled in Canada (and the west of the US) never fails to fascinate me. It’s unbelievable to picture some of the devastating losses many of these people experienced as well as raising 16 children like the Sigvaldasons! So interesting to get a glimpse into the homes, churches and stores and try to imagine the people who built them. Anita

Anita, what these settlers went through fascinates me too. I love finding out the stories in the old buildings.