Mounds and Canals: Hohokam History in Mesa, Arizona

Hohokam history in Mesa, Arizona at Sce:dagĭ Mu:val Va’aki and Park of the Canals

According to numbers from the U.S. Census Bureau, the Greater Phoenix area is the thirteenth largest metropolitan area in the United States, with a 2012 population of over 4.3 million people. Phoenix was first officially recognized as a community in 1868. In 1980, population numbers were under 2 million. Despite the relatively recent establishment and population growth, history of human occupation in the area dates back thousands of years.

The Hohokam peoples, ancestors of Pima-speaking Indians, occupied this area from about 300 BC into the first half of the fifteenth century AD. They settled in communities, built sophisticated irrigation systems, and were skillful farmers and creative artisans.

Two sites in Mesa, Arizona highlight the history and legacy of these people: Sce:dagĭ Mu:val Va’aki and Park of the Canals

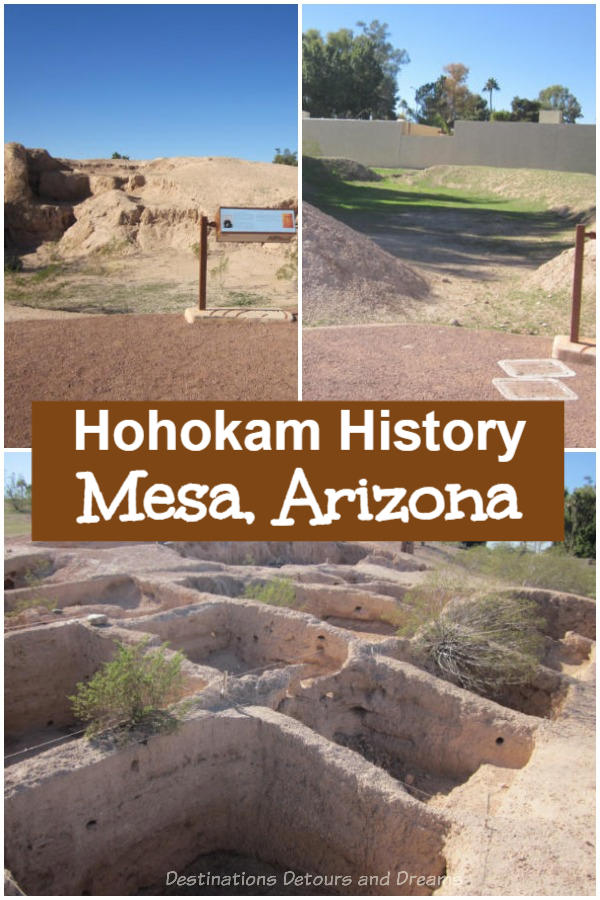

At first glance, you are unlikely to be impressed by either site. Just a mound of dirt and a ditch. The sites become more interesting when you look closer in the context of their history.

Sce:dagĭ Mu:val Va’aki

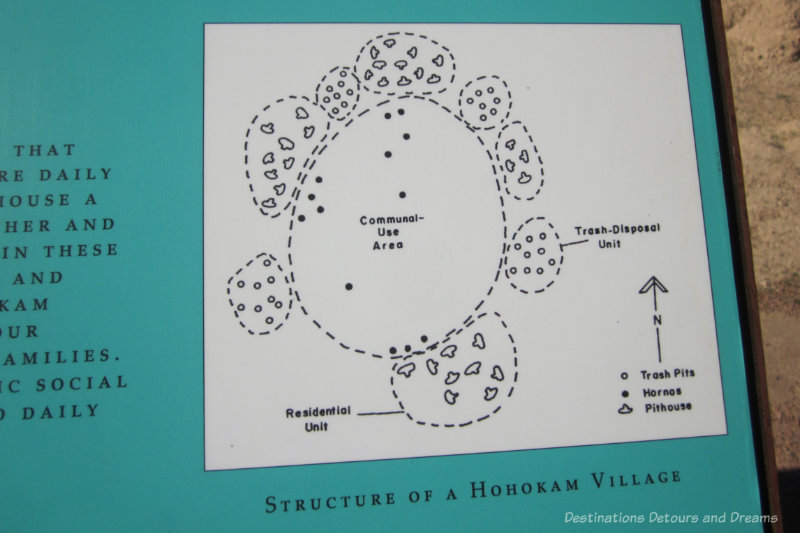

At Sce:dagĭ Mu:val Va’aki (formerly Mesa Grande Cultural Park), you’ll find the ruins of a temple mound built by the Hohokam between 1100 and 1400 AD. Two thousand Hohokam lived in the village around the mound, one of the largest Hohokam settlements in the Salt River Valley. Researchers believe that Hohokam platform mounds were either ceremonial centres or homes of the elite. Archeological work at Mesa Grande supports the idea of ceremonial centres.

The mounds were built in stages. The basic building block of the mound was a cell, a rectangular space with walls of caliche and no doors or windows. Caliche is a hard white material that forms underneath the desert soil. It was excavated and mixed with water to form a cement-like material. The cells were filled with compacted dirt to create the mound and rooms built on top and around the mound.

The square holes in the picture above are not prehistoric rooms. They are units excavated by Arizona Museum of Natural History and archaeology students from Mesa Community College. The walls between exposed units have been left in place so archaeologists can study exposed layers of soil.

A reproduction of a Hohokam ballcourt sits in the northwest corner of the park. The original Mesa Grande ball court is now buried underneath the Desert Vista Hospital northeast of the park. Hohokam ballcourts had large posts at each end, possibly serving as goal posts. The game was played with a small ball made of natural rubber. It is possible the courts were also used to promote market activities.

There is a small fee to visit Sce:dagĭ Mu:val Va’aki . Check the website for hours of operation.

Park of the Canals

The Hohokam relied on massive canal systems to irrigate their crops. Over 500 miles of Hohokam canals have been recorded in the Salt River Valley. Some canals were more than 12 miles long, up to 100 feet wide and 15 feet deep. The Park of the Canals displays over 1,400 feet of Hohokam canals in three different sections.

The cause for the disappearance of the Hohokam people from the valley around 1450 AD has never been established. In the late 1800s, Mormon pioneers discovered the ancient canals and cleaned out, rebuilt and re-used some of them.

There is also a small botanical garden, Brinton Desert Botanical Garden, at Park of the Canals.

Entrance to the Park of the Canals and the Brinton Botanical Garden is free.

PIN IT

Thank you Donna for the lovely online itinerary, I’ve never been to places like this and I am not sure I will ever see them in my life, so I’ve had a lovely journey today.

Donna,nice to know Hohokam sites. I never been to such places and I don’t think i will be lucky to visit similar one soon.

I love the desert and would love to live in such an environment, but that’s not going to happen given my husband hopes to transfer to rainy and gray Seattle. I first got interested in the desert by reading Edward Abbey, but O’Keefe’s work piqued my interest as well. There’s a harsh, but beautiful honesty in the desert that a forest can’t have.