Surrealism, Oddities and Beauty at the Dalí Theatre-Museum

Exploring the work of Salvador Dali at the Dali Theatre-Museum in Figueres, Spain

The Dalí Theatre-Museum in Figueres, Spain calls itself “the largest surrealistic object in the world”. I had expected to find surreal and unconventional art. I found that, but was surprised at the volume and breadth of work. Not only was Dalí prolific, his work spanned many genres.

The display of art starts with the exterior of the museum itself. Dalí painted the walls maroon and decorated them with yellow, plaster loaves of bread. Crimson and yellow are the colours of the Catalonia flag. Bread appears frequently in Dalí’s work. In his early works, it represented a staple in Spanish life. In later works, it took on sexual connotations. Dalí planted cypress trees in front of the museum. The eggs on top of the building represent birth and, therefore, symbolize hope and love. Eggs also appear frequently in Dalí’s work. I was told that the golden Oscar-like statues on top of the building represented wealth and fame. I visited the museum on a tour from Barcelona. Before he left us to explore the museum on our own, our tour guide suggested that the exterior of the museum was a bit of a joke by Dalí, indicating the wealth to be found in the United States. It was during Dalí’s time in the United States that he became most famous and wealthy.

The Dalí Theatre-Museum occupies the building of the former Municipal Museum, a 19th century building destroyed during the Spanish Civil War. Dalí purchased the site and devoted most of his time from 1960 to 1974 to creating the museum. By this time, Dalí had become known as much for his outrageously eccentric behaviour and self-promotion as for his art. It is certainly not a humble man who builds a museum dedicated to himself.

Salvador Dalí was born in 1904 in Figueres in Catalonia, an area Spain calls a region and Catalans consider “a nation without a state”. In 1922, he went to Madrid to study art, but was expelled in 1923 for criticizing his teachers and starting a riot. He returned to the school in 1926 and was permanently expelled before his final exams for declaring there was no one on the faculty competent to examine him. In the following years, he travelled frequently to Paris, where he met many influential painters and intellectuals. He became part of the Surrealism movement, but was expelled by other members in 1934, supposedly for quietly supporting Francisco Franco, the military leader who later became the dictator of Spain. During the 1930s, he travelled frequently to the United States and moved there when World War II broke out. He moved back to Catalonia in 1948.

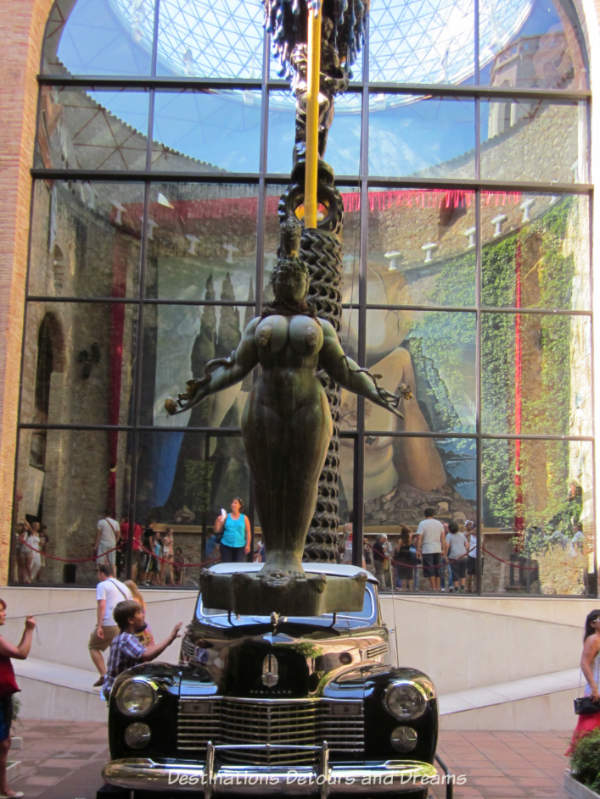

In the centre of an atrium, where gargoyles and golden statues of women decorate the ivy-coloured walls, is a black Cadillac. A mannequin bearing a resemblance to Elvis Presley sits inside the car. If you feed the coin box at the base of the car, it rains inside the car. Our tour guide pointed this out, saying Dalí liked money, a very Catalan trait.

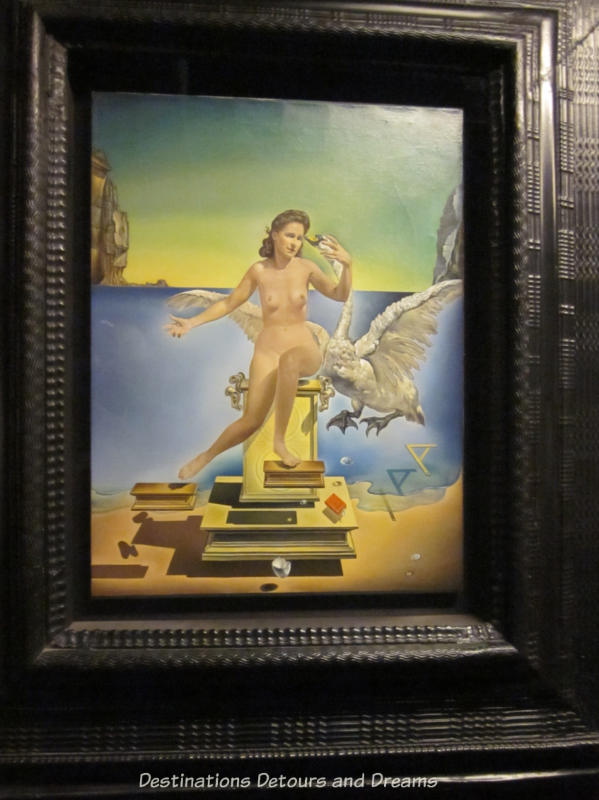

In 1929, Dalí met Gala, who became his life-long companion. They married in 1934. Dalí used Gala as a model for many of his paintings.

In the Mae West room, a lip-shaped sofa, a nostril-like shelf/sculpture, and two paintings on the wall combine to create an image of Mae West. I stood in line to climb onto a scaffold where I looked through a sculpted bower of blond hair to see the effect.

I was most intrigued by the painting Gala Contemplating the Mediterranean Sea which at Twenty Meters Becomes the Portrait of Abraham Lincoln. Our tour guide said you see the back of a woman looking out a window if you have good eyesight. If your eyes aren’t so good, you see a portrait of Abraham Lincoln. I saw a woman looking out the window, but when I took a photograph, the image in my viewfinder looked like Abraham Lincoln. When I downloaded the picture to my computer, I saw the woman again. Dalí painted two copies of this picture. The other hangs in The Dalí Museum in St Petersburg, Florida.

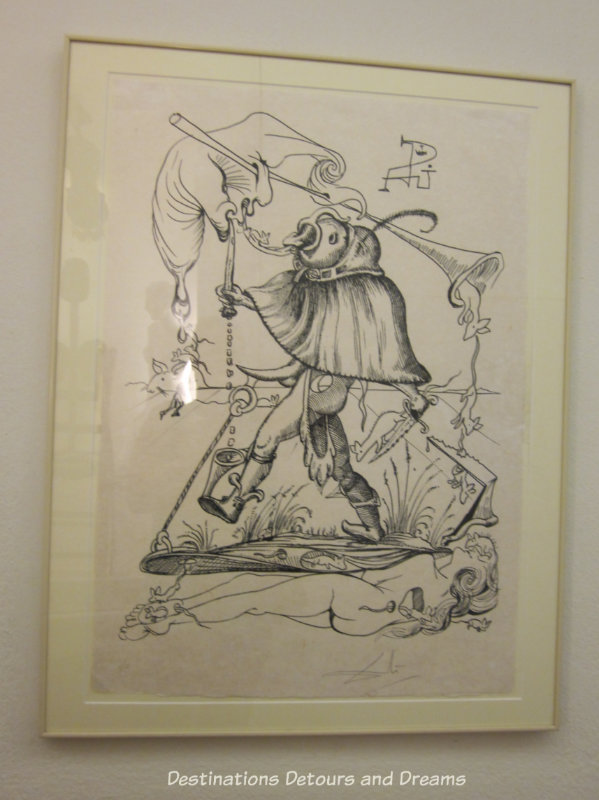

Dalí used symbols that recur throughout his work. Angels, breasts, ants, elephants, crutches, and limp watches, to name a few. There has been much written about the meanings of those symbols and what in Dalí’s life inspired them. Food appears often, purported to be the result of his childhood desire to be a cook. Seeing Dalí’s works makes me wonder what kind of chef he would have been, had his life taken that direction. Surely some type of fusion cuisine.

I found the volume of material at the museum overwhelming and somewhat exhausting. Dalí’s works contain symbolism and layers of meaning that make it difficult to take in all the pieces in one afternoon. I shuddered at some pieces. Some pieces I found too strange to comprehend. I’ve read that Dalí stood on his head to induce hallucinations as inspiration. Some pieces fascinated me. Some I found beautiful.

Dalí said, “This museum must not be seen as a museum, it is gigantic surrealist object, where everything is coherent and nothing escapes my meaning.” Dalí died in 1989 and is buried in a crypt in the museum.

One day it will have to be officially admitted that what we have christened reality is an even greater illusion than the world of dreams. Salvador Dalí

Destinations Detours and Dreams monthly e-newsletter contains behind the scenes information, sneak peeks ahead, travel story recaps and more. SIGN UP HERE

I was planning on going to Spain this month. Obviously, those plans changed. The atrium looks amazing.

Ken, I hope you are able to get to Spain when travel is safe again.